BRICKS AND STICKERS

“If I vibrate with vibrations other than yours, must you conclude that my flesh is insensitive?” -Claude Cahun, Héroïnes

The modern era is filled with testaments to poor aging. Eager to build in big and fast numbers, its architects were often quick to select untested material palettes. For many, what looked stunning and rigid with the scaffolding removed soon crumbled under its own weight. Quick to rise, quick to fall.

But Mies van der Rohe was famously one to be more vain than hasty. While many architects communicated their allegiances to industrial functionalism through the use of sturdy yet ultimately ruinous materials (such as poured-in-place concrete for grain elevators or self-oxidizing metal for factories), Mies preferred his buildings clad in anything that would allow them to last eternal. Here his trademark use of stainless steel and marble ring clear, though the heavy use of exposed brick in his early career seems at first glance to be contradictory with this ambition.

The Haus Lange, built in Krefeld, Germany in 1928 is a telling example. Unlike the hopeful purity of the usual modernist materials, the bricks of the Haus Lange were selected and stacked in a decidedly imprecise manner; a little chipped, and a little uneven. This was Mies’ method of ‘pre-aging’ the building, ensuring that the house would mature as contently as any other brick building before it. Peter Blake’s vilification of modernist materials adequately sums up Mies’ sentiments at the time: “Exposed, flat, poured-in place concrete surfaces will frequently stain and develop shrinkage cracks and are sure to look prison-grim under overcast skies, whereas brick and stone can look quite beautiful in a rainstorm.”

The decision might seem at odds with the times, perhaps not forward-thinking enough for the shrewd observer. As Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock point out in The International Style, "the use of [exposed] brick tends to give a picturesqueness which is at variance with the fundamental character of the modern style." But Mies was also more vain than adherent.

Despite the consequences, the one material he couldn’t avoid using - the one that ages just as poorly as concrete and exposed metal combined; the one that fogs up, streaks, scratches and warps - was glass. As dedicated as Mies was to conceit, he also couldn’t deny his clients natural light, and that meant lots of windows in places hard to reach. When the Haus Lange aged, the bricks stayed perfectly imperfect while the glass just became imperfect.

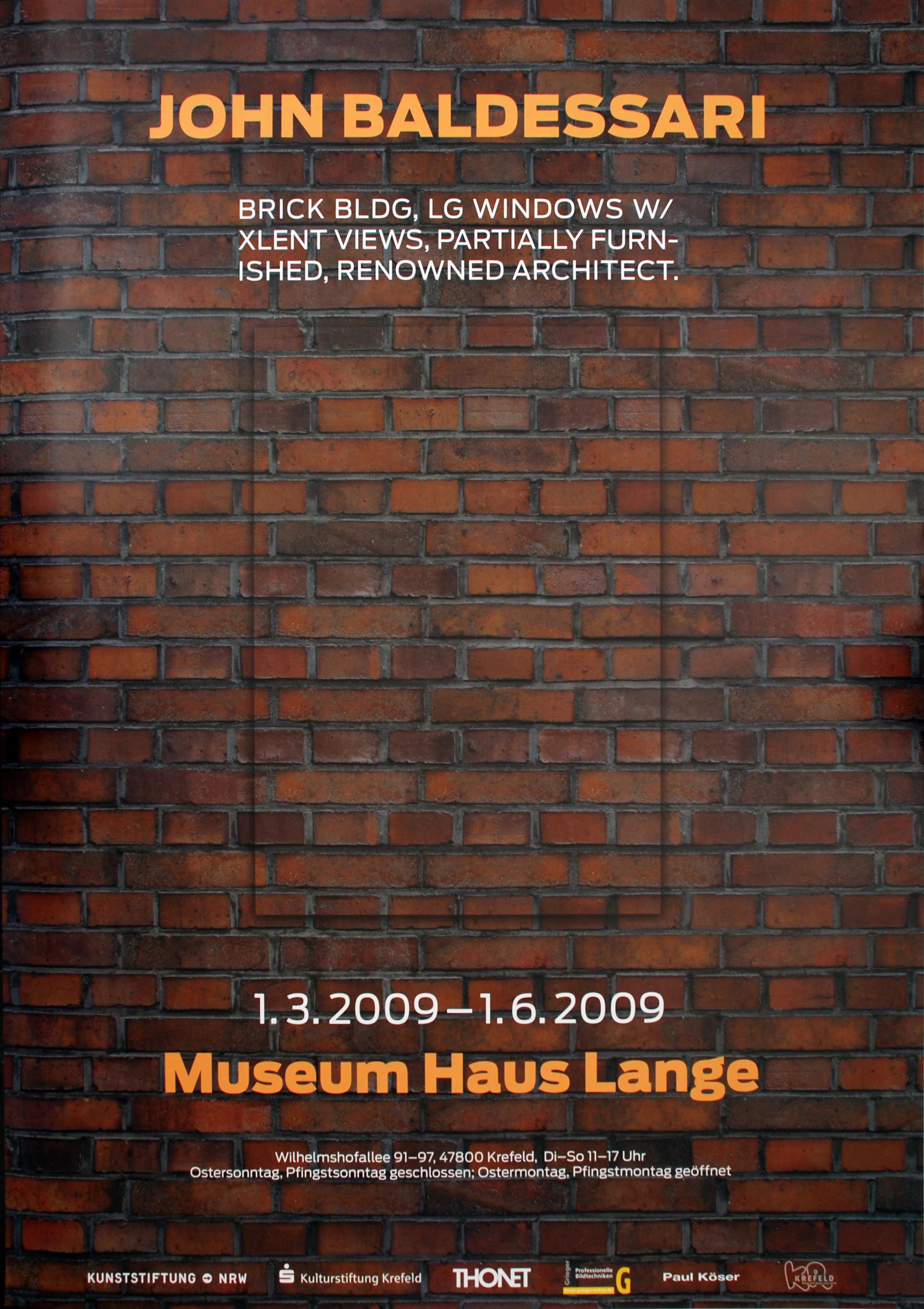

The house’s presence as a questionably aged object was challenged when it was converted into a contemporary art museum several decades later. In 2009, artist John Baldessari was given the keys to the conflicted building and potentially found a solution to Mies’ fear of aging.

For his installation, Baldessari covered the exterior windows with brick pattern peel & stick contact paper to match Mies’ original cladding. The visages effectively transformed the home into one large envelope of indecipherably various materials, one thick and the other flat. And because the photos on the contact paper were elevations of the then 81 year old Haus Lange brick pattern, they were, by transitive property, just as perfectly imperfect as the bricks they emulated. On overcast days, they shared the very same reddish hue.